There's been a Murder in SQL City! The SQL Murder Mystery is designed to be both a self-directed lesson to learn SQL concepts and commands and a fun game for experienced SQL users to solve an intriguing crime.

Walkthrough for SQL Beginners

If you're comfortable with SQL, you can skip these explanations and put your skills to the test! Below we introduce some basic SQL concepts, and just enough detail to solve the murder. If you'd like a more complete introduction to SQL, try Select Star SQL.

A crime has taken place and the detective needs your help. The detective gave you the crime scene report, but you somehow lost it. You vaguely remember that the crime was a murder that occurred sometime on Jan.15, 2018 and that it took place in SQL City. Start by retrieving the corresponding crime scene report from the police department’s database.

All the clues to this mystery are buried in a huge database, and you need to use SQL to navigate through this vast network of information. Your first step to solving the mystery is to retrieve the corresponding crime scene report from the police department’s database. Below we'll explain from a high level the commands you need to know; whenever you are ready, you can start adapting the examples to create your own SQL commands in search of clues -- you can run any SQL in any of the code boxes, no matter what was in the box when you started.

Some Definitions

What is SQL?

SQL, which stands for Structured Query Language, is a way to interact with relational databases and tables in a way that allows us humans to glean specific, meaningful information.

Wait, what is a relational database?

There's no single definition for the word database. In general, databases are systems for managing information. Databases can have varying amounts of structure imposed on the data. When the data is more structured, it can help people and computers work with the data more efficiently.

Relational databases are probably the best known kind of database. At their heart, relational databases are made up of tables, which are a lot like spreadsheets. Each column in the table has a name and a data type (text, number, etc.), and each row in the table is a specific instance of whatever the table is "about." The "relational" part comes with specific rules about how to connect data between different tables.

What is an ERD?

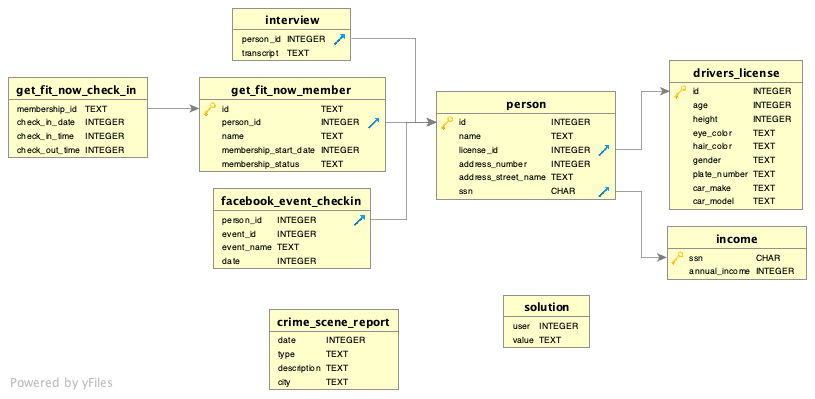

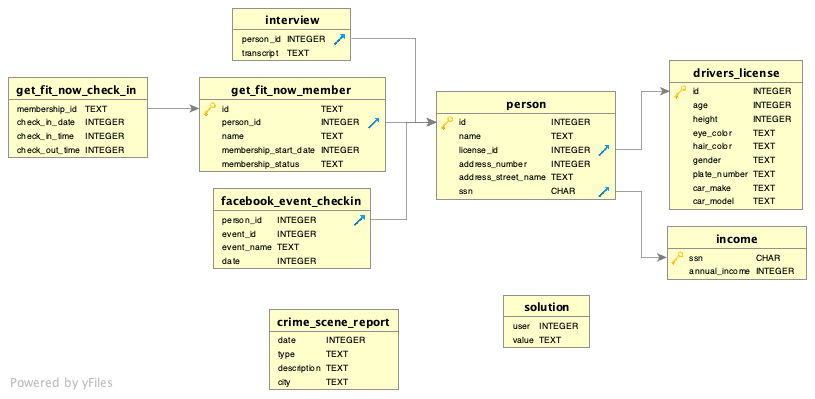

ERD, which stands for Entity Relationship Diagram, is a visual representation of the relationships among all relevant tables within a database. You can find the ERD for our SQL Murder Mystery database below. The diagram shows that each table has a name (top of the box, in bold), a list of column names (on the left) and their corresponding data types (on the right, in all caps). There are also some gold key icons, blue arrow icons and gray arrows on the ERD. A gold key indicates that the column is the primary key of the corresponding table, and a blue arrow indicates that the column is the foreign key of the corresponding table.

- Primary Key:

- a unique identifier for each row in a table.

- Foreign Key:

- used to reference data in one table to those in another table.

Here is the ERD for our database:

What is a query?

If you were to look at the data in this database, you would see that the tables are huge! There are so many data points; it simply isn’t possible to go through the tables row by row to find the information we need. What are we supposed to do?

This is where queries come in. Queries are statements we construct to get data from the database. Queries read like natural English (for the most part). Let's try a few queries against our database. For each of the boxes below, click the "run" to "execute" the query in the box. You can edit the queries right here on the page to explore further. (Note that SQL commands are not case-sensitive, but it's conventional to capitalize them for readability. You can also use new lines and white space as you like to format the command for readability. Most database systems require you to end a query with a semicolon (';') although the system for running them in this web page is more forgiving.)

What elements does a SQL query have?

A SQL query can contain:

- SQL keywords (like the SELECT and FROM above)

- Column names (like the name column above)

- Table names (like the person table above)

- Wildcard characters (such as

%) - Functions

- Specific filtering criteria

- Etc

SQL Keywords

SQL keywords are used to specify actions in your queries. SQL keywords are not case sensitive, but we suggest using all caps for SQL keywords so that you can easily set them apart from the rest of the query. Some frequently used keywords are:

SELECT

SELECT allows us to grab data for specific columns from the database:

- * (asterisk): it is used after SELECT to grab all columns from the table;

- column_name(s): to select specific columns, put the names of the columns after SELECT and use commas to separate them.

FROM

FROM allows us to specify which table(s) we care about; to select multiple tables, list the table names and use commas to separate them. (But until you learn the JOIN keyword, you may be surprised at what happens. That will come later.)

WHERE

The WHERE clause in a query is used to filter results by specific criteria.

Let's try some of these things.

The AND keyword is used to string together multiple filtering criteria so that the filtered results meet each and every one of the criteria. (There's also an OR keyword, which returns rows that match any of the criteria.)

If you haven't found the right crime scene report yet, click "show solution" above, and replace the contents of the box with just the revealed command. (Leave out the initial /*) If you figured out the query that shows the

single crime scene report instead of a few for the same city and type, then congratulations and disregard the word "incorrect". You'll know if you got it!

Wildcards and other functions for partial matches

Sometimes you only know part of the information you need. SQL can handle that. Special symbols that represent unknown characters are called "wildcards," and SQL supports two. The most common is the % wildcard.

When you place a % wildcard in a query string, the SQL system will return results that match the rest of the string exactly, and have anything (or nothing) where the wildcard is. For example,

'Ca%a' matches Canada and California.

The other, less commonly used wildcard, is _. This one means 'match the rest of the text, as long as there's exactly one character in exactly the position of the _, no matter what it is. So,

'B_b' would match 'Bob' and 'Bub' but not 'Babe' or

'Bb'.

Important: When using wildcards, you don't use the = symbol; instead, you use

LIKE.

SQL also supports numeric comparisons like < (less than) and > (greater than). You can also use the keywords BETWEEN and AND -- and all of those work with words as well as numbers.

We've mentioned that SQL commands are not case-sensitive, but WHERE query values for

= and LIKE are. Sometimes you don't know how the text is stored in the database. SQL provides a couple of functions which can smooth that out for you. They're called UPPER() and

LOWER(), and you can probably figure out what they do, especially if you explore in the box below.

Digging deeper

SQL Aggregate Functions

Sometimes the questions you want to ask aren’t as simple as finding the row of data that fits a set of criteria. You may want to ask more complex questions such as “Who is the oldest person?” or “Who is the shortest person?” Aggregate functions can help you answer these questions. In fact, you learned an aggregate function above, COUNT.

How old is the oldest person with a drivers license? With a small amount of data, you might be able to just eyeball it, but there thousands of records in the drivers_license table. (Try COUNT if you want to

know just how many!) You can't just look over that list to find the answer.

Here are a few useful aggregate functions SQL provides:

- MAX

- finds the maximum value

- MIN

- finds the minimum value

- SUM

- calculates the sum of the specified column values

- AVG

- calculates the average of the specified column values

- COUNT

- counts the number of specified column values

There's another way to find minimum and maximum values, while also seeing more of the data. You can control the sort order of results you get. It's really quite intuitive: just use ORDER BY followed by a column name. It can

be challenging when there's a lot of data! (When people get serious about working with SQL, they use better tools than this web-based system.) By default, ORDER BY goes in "ascending" (smallest to largest, or A to Z) order, but you

can be specific with ASC for ascending, or you can reverse it with DESC.

By now, you know enough SQL to identify the two witnesses. Give it a try!

Making connections

Joining tables

Until now, we’ve been asking questions that can be answered by considering data from only a single table. But what if we need to ask more complex questions that simultaneously require data from two different tables? That’s where JOIN comes in.

More experienced SQL folks use a few different kinds of JOIN -- you may hear about INNER, OUTER, LEFT and RIGHT joins. Here, we'll just talk about the most common kind of JOIN, the INNER JOIN. Since it's common, you can leave out INNER in your SQL commands.

The most common way to join tables is using primary key and foreign key columns. Refer back to the Entity Relationship Diagram (ERD) above if you don't remember what those are, or to see the key relationships between tables in our database. You can do joins on any columns, but the key columns are optimized for fast results. It is probably easier to show how joins work with our interactive SQL system than to write them.

Sometimes you want to connect more than one table. SQL lets you join as many tables in a query as you like.

Now that you know how to join tables, you should be able to find the interview transcripts for the two witnesses you identified before. Give it a try!

Go Get 'em!

Now you know enough SQL to solve the mystery. You'll need to read the ERD and make some reasonable assumptions, but there's no other syntax that you need!

Experienced SQL sleuths start here

A crime has taken place and the detective needs your help. The detective gave you the crime scene report, but you somehow lost it. You vaguely remember that the crime was a murder that occurred sometime on Jan.15, 2018 and that it took place in SQL City. Start by retrieving the corresponding crime scene report from the police department’s database.

Exploring the Database Structure

Experienced SQL users can often use database queries to infer the structure of a database. But each database system has different ways of managing this information. The SQL Murder Mystery is built using SQLite. Use this SQL command to find the tables in the Murder Mystery database.

Besides knowing the table names, you need to know how each table is structured. The way this works is also dependent upon which database technology you use. Here's how you do it with SQLite.

The rest is up to you!

If you're really comfortable with SQL, you can probably get it from here. We've also included some atmospheric music to get you into the mood! Press the play button and start the challenge.

But click here to show the schema diagram.

Check your solution

Credits

The SQL Murder Mystery was created by Joon Park and Cathy He while they were Knight Lab fellows. See the GitHub repository for more information.

Adapted and produced for the web by Joe Germuska.

This mystery was inspired by a crime in the neighboring Terminal City.

Web-based SQL is made possible by SQL.js

SQL query custom web components created and released to the public domain by Zi Chong Kao, creator of Select Star SQL.

Original code for this project is released under the MIT License

Original text and other content for this project is released under Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0